FOXBOROUGH, Mass. – Andrew Farrell was a five-year-old American kid at recess, and he didn’t speak a lick of Spanish. That might not have been an issue for you or me, but it was for Farrell, considering the fact that he was living in Peru at the time.

Farrell’s parents, steered by their work as missionaries, moved the family to South America in 1997. Suddenly this small child found himself in a Peruvian school where basic communication was next to impossible, making the complex transition to a new life in a strange land all the more complicated.

But the first time he went to recess, he quickly realized that he actually did share a language with his Peruvian classmates. The language didn’t involve words, but a ball and a goal.

Andrew Farrell spoke soccer.

“That made it click,” Farrell said. “At recess it was like, ‘Okay, there are kids kicking the soccer ball, let’s go play.’ Right away I became friends with everybody.

“It was just the language of the world and it makes it so much easier. You don’t even have to say anything; you’re just out there kicking the ball and having a good time.

“That’s my whole life; all my best friends are through soccer. Everything is through soccer.”

Andrew Farrell reacted the way you’d expect a five-year-old to react when his parents told him that they’d be packing up their life in America and moving to Peru for at least five years, maybe longer.

“I wasn’t happy,” Farrell said. “It just threw me off. I didn’t want to go; I wanted to stay. I had friends, my toys were here – everything.”

One of the biggest obstacles upon arrival in Peru, of course, was the language barrier. Farrell’s father, who had previously studied in Chile, already spoke Spanish, and his mother had a general grasp of the language. But five-year-old Farrell was still fully grasping the complexities of English.

While soccer helped ease the transition and earned Farrell acceptance among his classmates before oratory communication was possible, it was still going to be necessary to speak at some stage. It’s kind of become a basic tenet of human existence.

Rather than put Farrell in an English-speaking school and teach him Spanish on the side – which could’ve taken years – his parents decided the best course of action at that age was to enroll him in a Spanish-speaking Peruvian school to immerse him in the language and speed up the learning process.

It worked. Farrell estimates that within two to three months he was conversational and spoke enough Spanish to get by at school. It was a matter of necessity.

“That’s why they say that when you’re trying to learn a language, just literally go there, because you have to learn it,” said Farrell, who now speaks Spanish as well as he speaks English. “I literally didn’t know any Spanish when we were going down there, so it was kind of crazy. But it worked out.”

Language wasn’t the only hurdle, though. Farrell was still a kid who missed his friends and the familiarity of American life, and he estimates it took about six months before he finally accepted the reality of the situation and fully immersed himself in the Peruvian lifestyle.

And, unsurprisingly, soccer had a vital role to play in that process.

“Six months and I was loving it,” said Farrell, who spent a total of 10 years – ages five to 15 – in Peru. “It was just totally different than anything I would’ve expected as a five-year-old.

“It was just soccer all the time; running around, being able to go outside in the park and play soccer where it was just random people all the time. Great food. I loved it. It was a pretty cool experience.”

Farrell played soccer in the States, as well, before his family moved to Peru. But it wasn’t until he was engulfed by the soccer-mad Peruvian culture that he became obsessed.

“I was into soccer, but that really got me into soccer. That was like the switch,” Farrell said, snapping his fingers.

Part of that transition from soccer enthusiast to soccer fanatic was the ease of the game’s availability. It was everywhere. If you had free time, you filled it with soccer. Playing soccer. Talking about soccer.

Farrell’s first home in Peru was in San Borja, a suburb of the capital city Lima and not far from the South Pacific coastline. Along with his parents and older siblings – one brother and one sister – Farrell’s family lived in a two-story apartment with a spiral staircase.

“Kind of smallish for five people,” Farrell said, “but it was awesome.”

The best aspect of that apartment in San Borja, though, was its proximity to a local park. Just two blocks away at all times was a veritable oasis where children gathered at all hours of the day to play soccer.

There was no schedule, no kickoff time and no final whistle. Just the game, all the time.

“That’s how I met all the kids in the neighborhood,” Farrell said. “You’d just go out. We didn’t have cellphones or anything; you’d just go to the park at a certain time and you’d see who was there. After that they’d be like, ‘Okay, we’ll be back around this time,’ and you’d just go out and literally play until dark.”

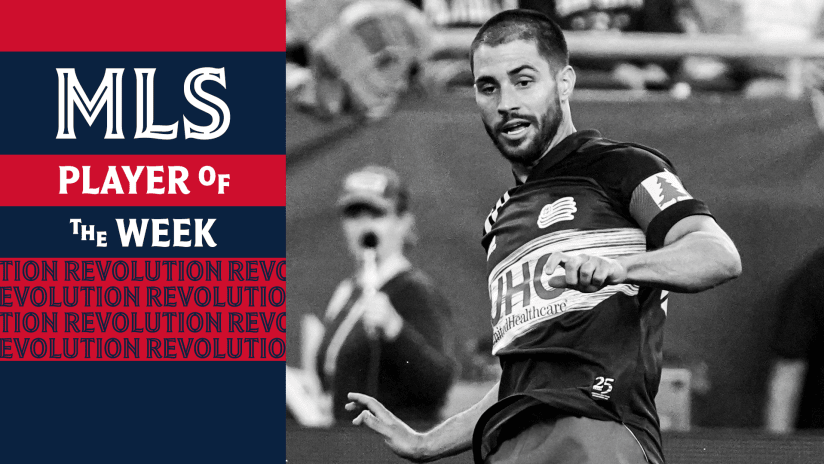

The influence of those childhood experiences is readily apparent in Farrell’s game, even now as a 23-year-old defender for the New England Revolution. Every time he acrobatically soars through the air to hit a bicycle-kick clearance, that’s Peru. The creativity and flair to take an opponent on the dribble – he learned that on that park in San Borja.

But the most important lesson Farrell learned in those early days playing pick-up in South America had nothing to do with skill, and everything to do with heart.

“Playing pick-up, you’re just enjoying the game,” Farrell said. “There’s not a lot of pressure. It’s not a tournament. It’s competitive – you want to win – but you’re enjoying it, you’re having fun, you’re getting to know people and different aspects of their life through the game.

“I’ll stop playing soccer when I don’t enjoy it anymore. That’s how I’ve always been. No matter if we’re running sprints or playing 5-v-2, I love being out there. I don’t see myself doing anything else.

“Just being outside and kicking the soccer ball around, it just makes me so happy. It sounds so weird, but [with soccer], I’m at my happiest I’ve ever been. I think that’s what I picked up from (Peru).”

So when you see Andrew Farrell hit an acrobatic clearance or go on a marauding run forward, that creativity and imagination is Peru. And the smile on his face as he does it? That’s Peru, too.

Farrell’s soccer education in Peru wasn’t limited to playing pick-up in the park. As he grew older he spent time with a pair of club teams – Tito Drago and Esther Grande de Bentin – and he fell in love with local professional side Alianza Lima and creative attacker Jefferson Farfan, his “favorite player of all time.”

A quick sidebar here. Farrell recently spent his 23rd birthday in Denver, where the Revs were preparing to play the Colorado Rapids. As the players rode the bus back from training, Farrell noticed Jermaine Jones chatting with Farfan – a former teammate of his at Schalke 04 – via FaceTime. Jones, aware that Farrell had grown up in Peru, called him over to join the conversation. Not a bad birthday present.

During the switch from Tito Drago to EGB – a bigger club with ties to professional side Sporting Cristal – Farrell hit somewhat of a crossroads. Growing pains in his knees sidelined him for an extended period, and he wasn’t featuring much upon his return, reduced to a spot on the bench.

The situation forced Farrell to step back and assess, and through that process he became stronger.

“At that point I was like, ‘Gosh, do I really want to push through this?’” he said. “There was a good four or five months where I was – not depressed, but I was like, ‘Should I focus on school?’

“That was a good time for me. It kind of pushed me to see if I actually wanted it. It was like the man upstairs asking, ‘Do you really want to do this? Let’s test you a little. Let’s do a little trial.’

“And I pushed through it.”

When he was 15 years old, Farrell’s family returned to the United States after a decade in Peru, settling once again in Louisville, Kentucky. And just as he had to adjust to life in South America as a five-year-old, Farrell once again had to adapt as a teenager in a somewhat foreign land.

And once again, soccer played a key role in that process. Farrell quickly made friends on the soccer field in high school before earning a scholarship to play at the University of Louisville, where he met one of his closest friends, Paolo DelPiccolo, on the soccer team. As he said, “Everything is through soccer.”

Farrell hasn’t returned to Peru since moving back stateside in 2007, but many of his Peruvian friends have visited him in Boston – some even attend Harvard and Boston University.

Farrell misses Peruvian food and the laid back culture of the country he called home for the majority of his childhood, but it’s the lessons he learned on the soccer field which might’ve served him best.

“You’ve just got to go,” Farrell said as he grasped for the right words to describe the special place Peru holds in his heart. “You’ve got to go down there.

“I love that my parents [moved to Peru]. I wouldn’t have changed it. I wouldn’t have hated being in the States, but it just made me who I am today.”